Adrienne Redd | ecoWURD oped

The environment is too seldom recognized for its central role in racial inequality over four centuries of social, legal and economic disadvantage in American history.

Broken public education, climate impact, and lack of fresh food are links in a chain of social causes and social problems that weigh disproportionately on BIPOC: Black, Indigenous People of Color.

We should understand that situational and cultural inequality (not intrinsic differences) produce inequities between Whites and BIPOC. Still, do we think of inequality as being a result of the contamination of air and water or the lack of access to fresh food – or that inequality contributes to the pollution of neighborhoods and that toxic contamination leads to more racial and economic inequality?

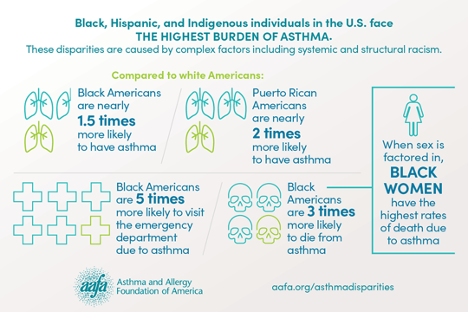

For example: are Black people, genetically, more predisposed to asthma? Of course not. It is more likely that the high incidence of respiratory disease in people of color happens because they have a greater chance of living near disposal facilities that spew poisons into their surroundings. One out of every 13 Americans have been diagnosed with asthma – and that’s rising. However, for African-Americans that number is one in nine largely as a result of where they reside.

Race, because of racism, becomes an indicator of poverty. Poverty plays out in neighborhoods. Poor, Black and Brown neighborhoods are where wastes get dumped. The dumping of pollutants creates negative health outcomes. Poor health costs money and contributes to economic hardship. Economic hardship and being non-White are statistically linked. And the cycle just keeps going on and on.

What exactly is environmental justice? Professor Robert Bullard, a social scientist at Texas Southern University, was among the first thought leaders to use the term in the 1970s and ‘80s. He showed that solid waste plants in Houston, Texas (and across the U.S.) are not evenly distributed, but sited in predominantly Black neighborhoods and near mostly-Black schools.

Institutionalized discrimination in the housing market, lack of zoning, and decisions by public officials have been major factors contributing to Black neighborhoods becoming the dumping grounds for trash and toxins.

Longtime Chester, PA concerned resident and activist Zulene Mayfield is a vivid storyteller of environmental injustice. She would tell you about it all in grisly detail, after having spent more than two decades fighting for cleaner, healthier spaces for the mostly Black and Brown residents of her hometown. It’s one reason she’ll also tell you why she doesn’t call herself an environmentalist. “I don’t call myself an ‘environmentalist.’ Mainstream environmental organizations just refuse to focus on the struggles of Black communities or see environmental struggles through a racial justice lens. They just don’t get involved in community of color battles, like they do animal & tree battles,” said Ms. Mayfield during a recent online conference hosted by Pennsylvania State Representative Napoleon Nelson (with ecoWURD as a partner and WURD’s Charles Ellison as keynote moderator). The event addressed environmental education, readiness for intensifying storms, energy transition, and the lack of available fresh food and how all of the above disproportionately attacks communities of color.

Nobody wants industrial discards or an incinerator in their backyard. That said, people can be overwhelmed and distracted by a snare of their own problems, including police brutality, inadequate schools, and less accumulated wealth than Whites. When the moment comes to protest at meetings on zoning permits or to hire capable lawyers, Black residents’ resources – time and money – have already been spent on more pressing household issues.

When striving to protect your teenager from police brutality, a parent may focus on urgent matters rather than, for example, the looming threat to health and home to climate change. Yet, these weather effects will ultimately accumulate and collapse on young people and people whose lives are the most precarious.

Contaminating the space in which people live creates an elaborate snowball effect of disadvantage – or what sociologists would call an “aggregate phenomenon.” Racial segregation of neighborhoods, even at times when it’s not part of a conscious conspiracy, leads to Black residents living in areas more likely to face degradation or blight. Dumping leads to poor health outcomes. Health effects can create cognitive disparities. Cognitive problems have social results. Social behavior has ramifications … and again a vicious cycle feeds on itself.

The connection between race and negative effects due to environmental degradation is true nationwide and can have a terrible cost in human potential. Studies in Michigan (where authorities switched to the Flint River as a water source) showed that lead poisoning was most heavily borne by low income communities, statistically more likely to be Black and Brown. Children with blood lead levels from 5 to 9 micrograms per deciliter had average IQ scores nearly five points lower than children exposed to less lead. And children with blood lead levels above 10 were three times more likely to be anti-social or hyperactive as children with lower levels. Is this because poor and non-White children are genetically less intelligent than Whites? Absolutely not. And yet, sadly, air and water quality are not immediately seen as major factors in educational, behavioral and social outcomes.

I started as an organizer by protesting against a mass burn incinerator and helping set up curbside recycling in my hometown of Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. We White activists were dismayed that our meetings and protests were all White (though the incinerator we defeated would have been nearest to the poor, Latino and non-White side of town). We just didn’t know what to do about it or how to frame the issue to the people who would be most affected.

The word “environmentalist” (like “feminist”) may have been contaminated by its suggestion of pious “political correctness” or bourgeois affectation. Environmentalism might seem like a frill to people whose lives face more immediate risks of racialized oppression. People of color may not immediately connect environmental policy to American racism because “environmentalism” is associated with love of nature, but nature is depicted as something out there, away and inaccessible – in the woods, in the mountains and not here where humans live day-to-day lives. In the face of more immediate deprivation, nature may not be considered central to well-being. It’s considered a very distant, unreachable luxury, like mansions of the super rich on a hill.

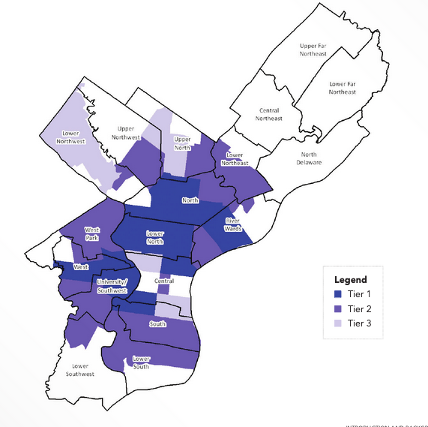

Race and poverty also affect availability of green space, proximity to where food is grown, and availability of fresh food. In all but very dense urban areas, the higher the percentage of BIPOC population, the more likely the area is a food desert, according to the USDA. The Northeast Development Corporation reported in December that food insecurity in Philadelphia has increased more than 16 percent in the past year, with the majority affected being – not surprisingly – people of color. High priority food insecure areas in Philadelphia are illustrated in the map below …

That same lack of availability of fresh food in poor, Black and Brown neighborhoods contributes to negative health outcomes, like obesity, high blood pressure and overall deterioration in quality of life. This is really what former first lady Michelle Obama’s was tackling with her program to reduce child obesity. Instead, it was lambasted by critics who made a political football out of it and trivialized what should have been a very crucial national conversation.

The need for awareness is why we’ve organized an “Our Environmental Future” series. We must make these conversations accessible to people who don’t necessarily consider themselves environmentalists. We’re looking for more Zulene Mayfields. Experts will speak to a number of key questions distressed communities are grappling with. For example, Tykee James, nature educator and Government Affairs Coordinator for the National Audubon Society asks: “How do we have these conversations about environmental awareness with our families and communities?”

That’s such an important question. It’s why we’ll need to elevate it by bringing together elected officials, educators, planners, and other advocates to talk about scientific and public education, climate response and food accessibility. It’s why we’ll help our communities and neighbors understand fully how these issues are connected to one another, and how it all leads to profound social and racial disadvantage. Once that connection is made, there’s nothing stopping us from finally making every space livable for everyone.

ADRIENNE REDD is an environmental advisor to State Representative Napoleon Nelson and an adjunct professor at the Community College of Philadelphia, whose courses include race, class & gender, social problems and anthropology.