Guest oped | Christina D. Rosan, Ph.D.

Too many Philadelphia residents live in the “struggle space.” It’s a place where daily struggles to survive resulting from histories of disinvestment and discrimination can create challenges for long-term climate planning.

So, what is it?

By the struggle space we refer to communities and residents whose primary focus is the struggle to survive. These are the overwhelming structural and racial injustices (historic, current and future) that too-often determine Black and Brown lives. As cities like Philadelphia now seek futures that are climate resilient and safe, they will need to make the struggle space a central part of their urban and climate policies. Too often residents living in the struggle space are forced to make choices based on their most basic needs and, for pragmatic reasons, are not able to focus on or fight for more long-term concerns like climate.

If the city does not proactively plan for climate justice, it will miss a critical opportunity to rebuild these communities with the protective green space they need to be resilient (and recreate). Reinvesting in neighborhoods that have suffered past and present injustices is critical for any climate planning. However, Black and Brown communities have been consistently marginalized by and excluded from planning and decision-making. To ensure that past mistakes are not repeated, climate planning needs to empower and engage these same communities.

The impacts of racism and injustice can be measured in the persistent ways that they determine people’s quality of life today, often along sharply drawn racial lines. Philadelphia’s Black and Brown residents talk of the “raw deal” that communities of color continue to experience. The terms of injustice change for these communities:

- Redlining and disinvestment have given way to gentrification and greening and the associated displacement;

- Unregulated development threatens historic buildings, neighborhood character and community green spaces; and

- Environmental hazards such as trash, dumping on vacant lots, lead and asbestos in schools and homes, and air pollution negatively affect community health.

The city currently has a variety of plans and commitments that highlight racial, social and environmental justice as well as climate change mitigation and resilience. But Philadelphia’s politicians and policymakers have yet to codify that. There are no firm institutional changes. They have not made the necessary governance changes that will lead to a more equitable, anti-racist, environmentally sustainable city.

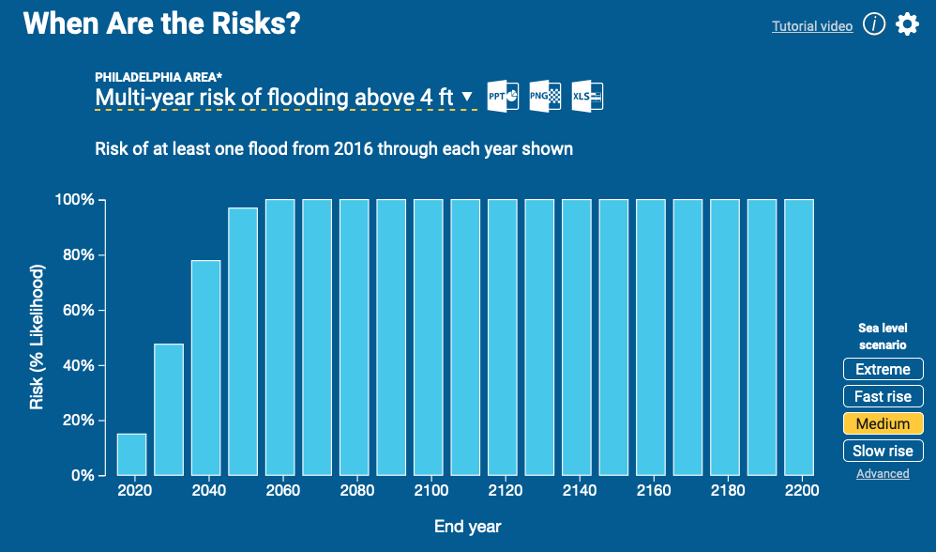

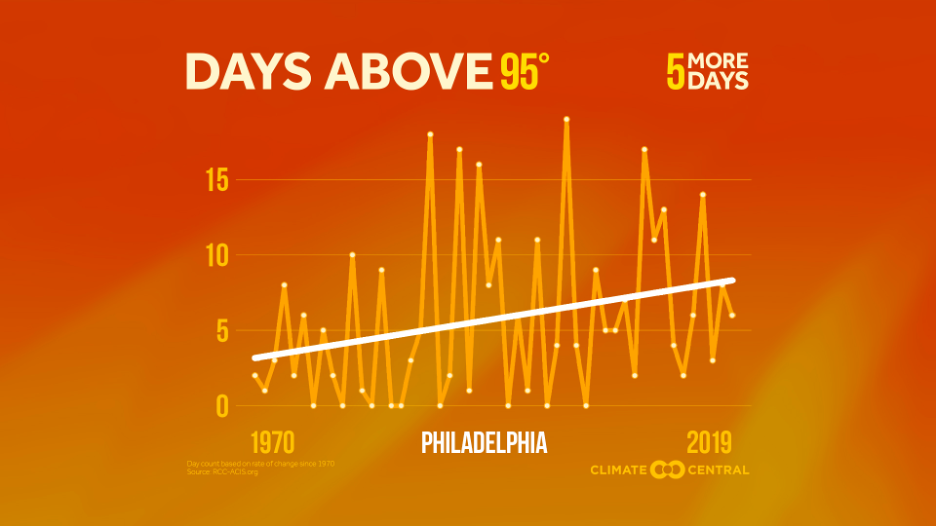

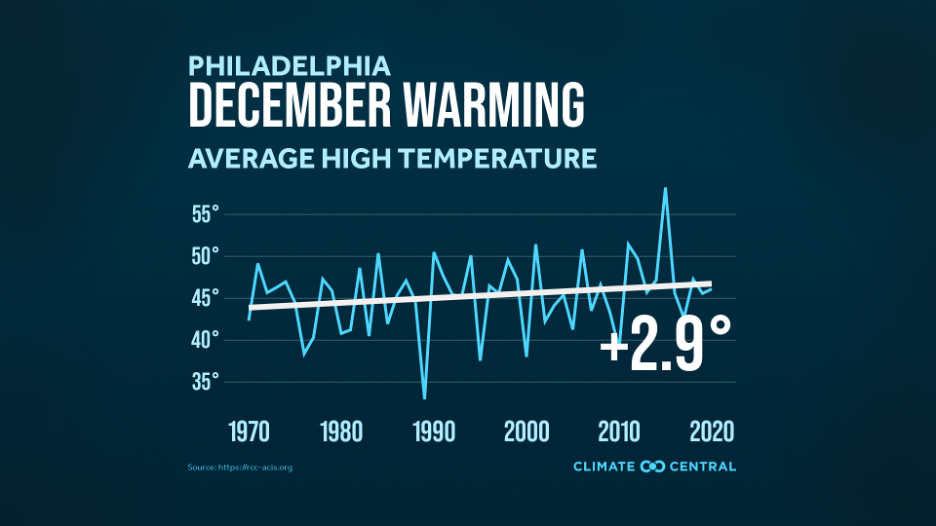

Looking to the future, climate vulnerabilities will exacerbate inequalities. The city of Philadelphia will be wetter and hotter, and the (mostly Black and Brown) neighborhoods of the struggle space that already lack tree cover, parks, open space and adequate weatherization and air conditioning will be the hottest and most vulnerable. These are the same communities that were redlined, demonstrating a direct link between past planning injustices and current and future vulnerabilities.

To then plan for a just climate future, the city needs to urgently address rapid gentrification and development and plan for livable and equitable communities for the people who are here already. Actions must be taken quickly. Rents and property taxes are rising. Vacant land is being rapidly redeveloped. If the city plans for greening without addressing housing and city tax policies, it risks “green gentrification” and displacement. This conundrum can be solved by intentional, progressive, anti-racist, anti-displacement, intersectional and coordinated planning.

Reaching those goals will entail low-income residents benefiting from neighborhood improvements without being priced out of their communities. The city needs proactive policies that protect and stabilize affordability, such as rent control, ending the new construction property tax abatement, reopening the Philly First Home program and expanding public housing. Previously, Philadelphia’s Black communities were victimized by redlining, which disinvested and prohibited investments in neighborhoods of color via institutionally codified banking practices. Non-white Philadelphians still feel the negative effects of this as housing stock continues to deteriorate in underserved communities amid the increasing effects of climate change.

The city must now ensure that greening and livability initiatives are connected with reducing the Black-white wealth gap by providing access to low-cost capital for home purchase. It also must ensure equal access to mortgages, home repairs, weatherization and energy efficiency. Meanwhile, the city also could play a pivotal role in training and incentivizing Black and Brown-owned businesses to improve climate preparedness and greening. If neighborhoods need green space, vacant land should be identified and protected for green space redevelopment. If the space needs to be maintained, Black and Brown-owned businesses should be hired for that important work. The same goes for developing and protecting affordable housing and ensuring longer-term affordability.

Improving public health and making neighborhoods more resilient to climate change should economically uplift communities — not raise rents and property values so that lower-income residents are priced out of safe communities. Expanding green space and other recreational space must be accompanied by economic policies that keep current residents in their homes. A Neighborhood Bill of Rights where residents identify what they want to see in their communities is one way to connect concerns about the struggle space and lack of neighborhood amenities with the opportunities of climate policy investments. We have also developed a Green Infrastructure Equity Index that was designed to identify community need for green stormwater infrastructure.

The only solutions to climate change that will work in Philadelphia are those that address the extreme racial and income inequality that has dominated the city and region in the post-industrial era, forcing generation after generation into the struggle space.