Dr. Charles Magee | ecoWURD oped

Recent events and policy debate surrounding the present condition of Black farmers in America compels a crucial historical review of how they arrived at this point. Knowing that history not only empowers us with more knowledge about the Black farming community and answers questions about the effectiveness of recent federal relief, but it also offers a roadmap for how African Americans could potentially dominate the food, agriculture and engineering sciences in the 21st century. This is a very important conversation given the challenges posed by climate change, food insecurity and inequality. Agriculture offers a solution.

Beginnings & Land Grant Institutions

The past history of African American involvement in agriculture in the United States began, of course, in 1619 when the first enslaved Africans were brought to the North American colony of Jamestown, Virginia to aid in the production of such lucrative crops as tobacco. American colonies in the 17th and 18th centuries, and enslaved Africans helped build the economic foundation of a new nation. When the Cotton Revolution began in 1690, African Americans were the engine, tragically, that made the United States the greatest cotton producing nation in the world. During the Civil War, from 1861-1865, more than 700,000 Americans lost their lives over keeping African Americans in bondage and toiling away on America’s cotton fields.

After the Civil War, nearly four million enslaved African Americans found themselves in a state of quasi-freedom. Quasi-free because the former slaves went from outright slavery to a forced plantation or share-cropping system. These former slaves had no money, no animals, no material properties of value and no formal education. However, they did possess empirical knowledge and memory from their cultural homeland on the continent of Africa, particularly West Africa, on the production of such crops as cotton, tobacco, rice, and peanuts. To keep from starving, the former slaves had to accept this quasi slavery arrangement while remaining in the most dire conditions.

In 1862, Congress passed a land-grant bill that had been introduced by Congressman Justin Smith Morrill from the state of Vermont. On July 2, 1862, President Lincoln signed the land-grant bill into law and it became known as the Morrill Act of 1862. The Act provided for the establishment of an institution of higher learning in each state that was mandated to include the teaching of agriculture and the mechanical arts among their academic offerings. No African Americans were allowed to attend these institutions. However, members of the White industrial class were allowed to attend and receive an education in agriculture, along with other academic disciplines offered.

Recognizing the precarious conditions of the former slaves and a possible humanitarian calamity in America, Congressman Morrill introduced a second land-grant bill in 1872 to establish a set of institutions for higher learning that would offer academic disciplines in agriculture and the mechanical arts for former slaves and their descendants. These institutions were located in states where African Americans could not legally attend the White land-grant institutions established under the 1862 Land-Grant Act. The second land-grant bill did not pass Congress until 1890, and it was signed on August 30, 1890 to became known as the 1890 Second Morrill Act for the Negro Citizens of America. Eighteen institutions were originally established under the Second Morrill Act. The right to teach agriculture and the mechanical arts at 18 institutions was the only tangible reparation African-Americans received after 246 years of slavery. These 18 institutions made a significant contribution to the formal education of African Americans in agriculture and many other disciplines. Black farmers became very proficient in the production of cotton, tobacco and peanuts.

Black Land Ownership Now & Then

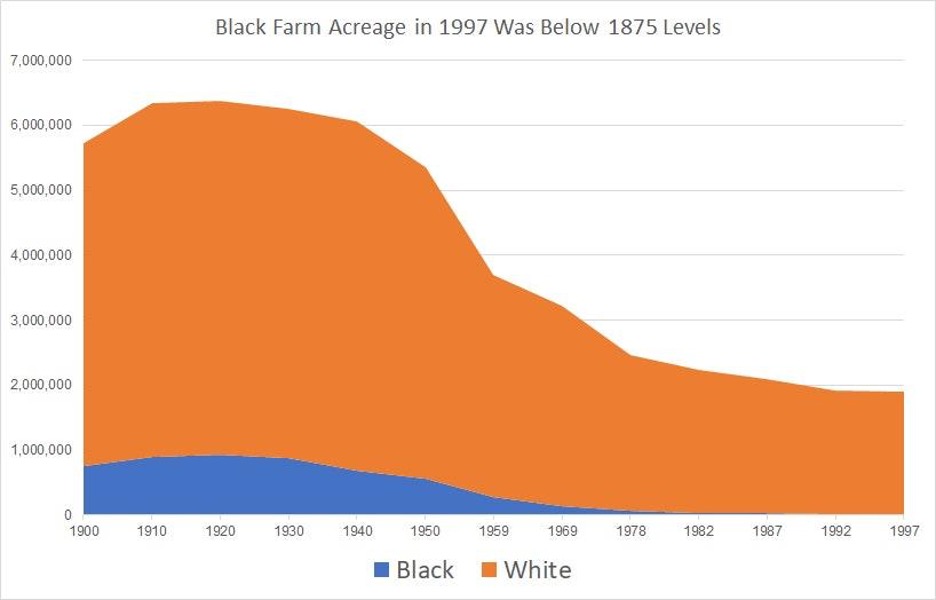

During the decade between 1920 and 1930, there were more than 900,000 Black farmers in the U.S. – and they owned more than 15 million acres of farmland. This decade was the apex of Black farmers and farmland ownership. To put this in perspective: Today African Americans, collectively, own fewer than four million acres of land.

Why is farmland ownership so important to Black communities? We all have heard that old adage: “Give a man a fish and feed him for a day. Teach a man to fish and feed him for the rest of his life.” However, if you don’t own the lake, it doesn’t matter how good your fishing skills are, you will still go to bed hungry. African Americans are becoming a landless people. Another adage often stated is: “A nation without a vision will perish;” well, an analogous statement is: “A race without land and people educated in the food, agricultural, and engineering sciences will also perish.” Every race should have the knowledge and skills to feed itself. And, for any nation to become a great nation, it must be able to feed itself and educate its people.

After Black agricultural production reached its zenith in the 1920-1930 decade, a decline started during the Depression. This author believes that United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) policies contributed to this steep decline in Black farmers and farmland loss.

The Cotton Allotment Policy

One particular policy that may have had the greatest negative impact on African American farmers was the Cotton Allotment Policy instituted in 1933. Similar policies were later developed and implemented for tobacco and peanuts. Black farmers were actually very proficient at producing all crops. Note that these crops were mainly grown in the Southwest, South, and Southeast region where you had the greatest number of African American farmers. Further, during the Depression, cotton prices were very low and the USDA attributed the low prices to an over production of cotton.

The USDA thought that a remedy to the overproduction of cotton was to limit the number of acres for each cotton farmer. Yet, in the 1920s and early 1930s, Black farmers were very proficient in producing cotton due to their long empirical knowledge of cotton production from slavery, share-cropping and the plantation system of farming. Furthermore, African American farmers had large families, which served them well as a source of labor for planting, cultivating, weeding and harvesting of cotton.

In the 1920s and 1930s, the two main ingredients for good cotton production were large acres of fertile land and a large labor pool. Logic would dictate that when the USDA put the Cotton Allotment Policy in place, it took away the incentive for African American farmers to acquire more land for cotton production. The White cotton producers had large acres of land; therefore, they were able to circumvent the limiting acreage policy by deeding some acres of land to their children and each child could receive a cotton allotment. Many of these children had no knowledge, equipment, or skills for cotton production. Thus, the family patriarch would continue farming the same number, if not more, of acres.

The Cotton Allotment Policy more than likely enhanced and perpetuated the share-cropping system of farming. Out of necessity, many African American families had to enter into a share-cropping arrangement with their White neighbors to increase their cotton production acreage. However, the African American family did not share in the USDA payment for taking cotton land out of production. All of the money went to the White land owner.

The Great Migration

The great migration of Black populations in the 1950s and 1960s from the South to the Northern states for better jobs and economic opportunities further lead to the decline of African American presence in production agriculture. During this period, agriculture was becoming heavily automated and mechanized. Tractors replaced mules and horses for planting and cultivating, chemicals replaced hoes for the removal of weeds, and cotton harvesters replaced humans for picking cotton. When the food and agricultural system depended largely on manual labor, African Americans were well represented. But, African Americans were virtually left behind when production agriculture became mechanized and automated.

Given our past negative history associated with the food and agriculture system, why should Black people consider a major or career in the food and agricultural sciences? There are several reasons why we should obtain degrees in the food, agricultural, and engineering sciences, including …

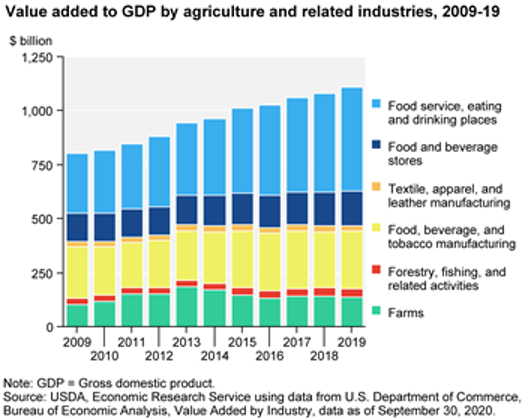

- Human beings and societies must eat to survive, that won’t change. Hence, agriculture is where the future and present jobs are. If you don’t think there are jobs associated with agriculture, next time you visit your local supermarket, ask yourself: How did the 10,000 plus food products get there? Very few African Americans are involved in the fields and professions required to make these 10,000 plus products possible. Yet, the USDA estimates that “… [a]griculture, food, and related industries contributed $1.109 trillion to the U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) in 2019, a 5.2-percent share. The output of America’s farms contributed $136.1 billion of this sum—about 0.6 percent of GDP.”

- Perhaps the greatest reason for many to pursue degrees and careers in the food, agricultural and engineering sciences is our social and moral obligation to help our brothers and sisters who still derive their living from the land on a full-time basis. Black farmers are becoming an endangered species. We should always remember: “No race or nation can be completely free if all its groceries are in someone else’s pantry.”

- Hypothetically, if we, African Americans, were to become a separate country, it would be the third or fourth largest Black nation in the world, with a population of nearly 50 million. However, we would still be at the mercy of other races because we wouldn’t have enough Black farmers, food and agricultural scientists and engineers to feed ourselves. We will never prosper as a race until we learn that there is as much dignity in driving a tractor as there is in driving a luxury car.

Black Excellence … In Agriculture

In order for African Americans to have lucrative careers in the food, agricultural, and engineering professions, we must first obtain degrees at all levels (bachelor’s, master’s, and doctorate) in these STEM disciplines. Lack of money should need not be a problem in deciding to pursue these degrees because at an 1890 Land Grant institution like Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University (FAMU), the College of Agriculture and Food Sciences has more scholarship funds than any other college at the University. Yet, we have a very difficult time in finding qualified students to take advantage of these scholarships.

We should have a plethora of African American peanut butter scientists in this county because during Black History Month, elementary, junior high, and high school students will identify George Washington Carver as a great Black scientist who is renowned for developing more than 100 products from peanuts. Yet, his face does not appear on the jar of any peanut butter. This should prompt you to wonder why so few Black people follow in the footsteps of Mr. Carver. Probably, not a single person reading this article can name a living Black peanut butter scientist. Our society will put an African-American cook and athletes’ faces on food products and other items, but it will not put Mr. Carver’s face on a jar of peanut butter.

On a broad scale, in food and agriculture, as a group of people, we have not made much progress because all we have done is go from “Miss Ann’s” kitchen to “Mr. McDonald’s” kitchen. If you don’t think this is the case, just visit any fast food place in the South. On the other hand, maybe we have made some progress, because today both Q’Erra and Jamal are working in “Mr. McDonald’s” kitchen. There is nothing wrong with working in a fast food kitchen, but we need more Black people working in the food testing, creation and research kitchen rather than the serving kitchen.

Prior to desegregation only Black women were allowed to work in “Miss Ann’s” kitchen. During the days of segregation, if you saw an adult Black man with a suit and tie on at 3 p.m., on a Monday afternoon, you knew he was either a school teacher, preacher, or he was probably one relative short. Thank God those days are gone. However, very few African Americans are taking advantage of the educational and career opportunities in the food, agricultural, and engineering sciences. Hopefully, this conversation has presented a cogent case for why we need to increase the pool of African Americans pursuing degrees and careers in the food, agricultural, and engineering sciences.

- CHARLES MAGEE is a professor in Agricultural and Food Sciences at Florida A&M University.