The planet is facing dual crises: the steep decline of nature and a rapidly changing climate.

Ryan Richards | Center for American Progress

Greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere are higher today than at any point previously in human history. At the same time, communities are losing natural areas to development at a rapid rate, and animal and plant species are being pushed to extinction 1,000 times faster than before humans were present.1

There is a growing understanding that the existential challenges facing the planet are interconnected; one cannot solve the climate crisis without addressing the nature crisis, and vice versa. They are, in fact, two sides of the same coin.

There is also a growing scientific consensus that, in order to confront the biodiversity crisis, the world must protect at least 30 percent of the earth’s lands and oceans by 2030—or “30×30.”2 Research suggests that investing in nature is essential to kickstarting progress toward the 2050 climate goal of net-zero emissions that will keep global temperatures from rising by more than 1.5 degrees Celsius.3 To that end, recent comprehensive climate plans—including one by the U.S. House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis—recognize the 30×30 goal as a critical plank in the platform.4 In the United States, only 12 percent of lands are considered protected. Oceans fare slightly better, with 23 percent considered strongly protected, but the vast majority of ocean protections are found in the remote Western Pacific region.5

Forests and other lands in the United States today draw out of the atmosphere and sequester, on net, more than 770 million metric tons (MMT) of carbon dioxide equivalent—equivalent to more than 11 percent of the country’s annual greenhouse gas emissions in the United States.6 If managed appropriately, research shows that they have the potential to store an additional 1,000 million tons of carbon dioxide equivalent annually, although these benefits arrive gradually as forests grow and land use changes.

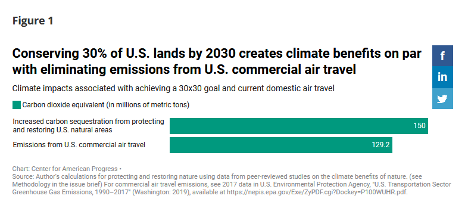

In this issue brief, the Center for American Progress shows that immediate conservation policy changes in pursuit of a 30×30 goal will not only set the United States on track to realize this level of carbon sequestration in the long run but also will deliver immediate emissions reductions. This first-of-its kind analysis estimates how much greenhouse gas emissions could be avoided if the United States successfully pursued a 30×30 goal. It finds that by avoiding the loss of existing natural areas though better protections and increasing the capacity of natural places to sequester carbon through ecologically sound restoration and reforestation, U.S. lands could absorb more than 150 MMT of carbon dioxide equivalent above today’s baseline every year by 2030.7 In other words, the magnitude of climate benefits from achieving a 30×30 goal in this country are comparable to eliminating the amount of annual emissions from commercial air travel in the United States.8

There are myriad reasons to protect more nature, from biodiversity concerns, to environmental justice, to outdoor recreation, to the economy, to health benefits, to ecosystem services. This issue brief provides new data that highlight another compelling reason: Protecting and restoring land in the United States can meaningfully contribute to solving the climate crisis.

Step one: Protect existing natural areas

The United States loses a football field’s worth of natural areas every 30 seconds due to the growing footprint of roads, housing subdivisions, oil and gas development, agriculture, and other human activities.9 Protecting 30 percent of U.S. lands by 2030 will help slow the rapid pace of natural area conversion that is contributing to the nation’s rising greenhouse gas emissions. Protecting ecosystems from development keeps the carbon that is already sequestered in plants and soil out of the atmosphere. Keeping land in its natural state also allows it to continue storing carbon, pulling more greenhouse gases out of the atmosphere.

Every ecosystem has some potential to mitigate the effects of climate change. Plants sequester carbon and store it into the future. This carbon is often stored in living wood—forests might come to mind when thinking about climate solutions—but is also held in soil, plant roots, and wetlands. How much carbon each ecosystem can store varies with geography, local climates, and ecological history—for example, the age of a forest.

CAP calculates that establishing new protections toward a 30 percent goal could capture at least 34 MMT of carbon dioxide equivalent annually by 2030. This number is a combination of carbon already stored in natural areas vulnerable to development and future carbon sequestration secured by protecting these natural areas:

- Protecting carbon stored on vulnerable lands: If the United States achieves an 80 percent slower rate of natural area loss as part of a 30×30 goal, the country would avoid the conversion of more than 1.2 million acres of natural areas per year. That means at least 22 MMT of greenhouse gas equivalent would remain stored in forests and other natural areas in 2030 instead of being cleared for human use.

- Safeguarding sequestration: These additional land protections would also boost the annual amount of sequestration that U.S. lands provide. By 2030, the authors expect that an additional 12 MMT of greenhouse gases would be captured each year by the 12 million acres of vulnerable lands that will be protected from development over the coming decade.

Step two: Restore forests, wetlands, and other places to their natural state

Reforesting and restoring natural areas can also have significant climate benefits by expanding the nation’s existing carbon sink. In fact, CAP estimates that targeted, science-led, ecological restoration to improve the condition of protected lands could increase the sequestration capacity of ecosystems by at least 117 MMT of carbon dioxide equivalent each year.

Restoring ecosystems means management that returns them to something closer to their historical ecological state. This helps natural places function in ways that benefit native plants and animals and often increases their capacity to store carbon in the long term. In many Western forests and grasslands, restoration reduces the risk of uncharacteristic wildfires, which are a public safety threat as well as a major carbon source. In floodplains and along coastlines, restoration helps protect communities during floods and storms.

Millions of acres have been altered by human actions such as logging, wetland dredging, and fire suppression. Restoring these places often means returning to historic fire patterns, animal and plant communities, and forest structures. Opportunities abound for investing in restoration across the country, which will create jobs and protect nature while also storing carbon:

- Reforestation: Recent research has found that at least 20 million acres of lands are in need of reforestation—meaning that they were historically forested but currently have no tree cover.10 More than 8 million of these acres are on federal lands. CAP calculates that a science-led, ecologically sound approach to addressing this backlog—by planting an additional 1 million acres per year to reflect the land’s historical ecological state—would result in at least 20 MMT of additional annual sequestration in 2030.

- Restoration of national forests: In addition to reforestation in places where forests have been lost entirely, the U.S. Forest Service estimates that it has a restoration backlog of 65 million to 82 million acres on national forest land.11 These are natural areas that do have tree cover but which no longer reflect their historical appearance and function, often because of fire suppression or decades of logging.12 In the past, CAP has recommended the revival of the Civilian Conservation Corps along with increased funding to manage national forests for the clean water, recreation, and wildlife benefits they provide.13 Increasing investments to restore the ecology of 6 million acres of national forest lands per year—as part of a long-term strategy that protects standing, ecologically important forests on federal lands as anchors of America’s natural carbon sink*—would sequester an additional 17 MMT of carbon dioxide equivalent in 2030.

- Accelerated restoration on private lands: Engaging private landowners in conservation and restoration is key to solving the conservation and climate crises. Millions of acres of private lands are already protected by land trusts or through conservation easements,14 and CAP has recommended that the U.S. Congress commit to funding conservation of at least 55 million more acres of private lands in pursuit of a 30×30 goal.15 Other groups, including the Land Trust Alliance, support similar targets.16 CAP has also proposed increasing funding for the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s conservation programs—including the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP), the Regional Conservation Partnership Program, the Conservation Stewardship Program, and the Environmental Quality Incentives Program—to restore already protected private lands and protect habitats in agricultural areas.17 Restoration on private lands, through planting of native species or other management practices, could conservatively sequester an additional 70 MMT of carbon dioxide equivalent while supporting jobs in the restoration economy across the country.

- Restoring floodplains and wetlands: In many parts of the country, climate change is already being felt as stronger storms and bigger floods push the United States’ river infrastructure of dams and levees to the limit. Restoring floodplains and coastlines will protect homes, lives, farmland, and the wetlands that are powerhouses for carbon storage.18 Dedicating federal funding to major green infrastructure projects and restoring mitigation programs that have been undercut by the Trump administration would sequester an additional 4 MMT of carbon dioxide equivalent in 2030.

- Investing in urban and community forests: Research has shown that communities of color, families with children, and low-income communities are significantly less likely to have access to nature.19 Working toward a 30×30 goal provides an opportunity for policymakers to proactively address this nature gap. The creation of new urban parks, recreation areas, and natural places near communities experiencing nature deficits—and the reforestation and restoration necessary for stewardship of these open spaces—will not only help ensure equitable access to the outdoors but could also sequester 6 MMT of carbon dioxide equivalent by 2030.

Conclusion

Addressing the climate crisis requires a holistic shift in how the United States manages the economy and governs society—and that includes how it commits to conservation of the natural world. Although the focus on transportation, electricity, and other sectors of the economy is critical, America should not overlook one of the most cost-efficient and effective tools it has available: protecting more nature. Conserving and restoring natural areas in pursuit of a 30×30 goal will quickly protect and expand America’s carbon sink and should be central to any strategy to address the climate crisis—a tried-and-true solution to pull carbon out of the atmosphere, while also benefiting the land, water, wildlife, and communities that rely on healthy natural systems.

RYAN RICHARDS is a senior policy analyst for Public Lands at the Center for American Progress. This brief originally appeared in the Center for American Progress and was the subject of a “CAP Corner” interview on WURD’s “Reality Check.”