A study shows dangerous racial and economic disparities in the destruction and protection of nature in America

Jenny Rowland Shea & Shanna Edberg | original Center for American Progress

Clean drinking water, clean air, public parks and beaches, biodiversity, and open spaces are shared goods to which every person in the United States has an equal right both in principle and in law. Nature is supposed to be a “great equalizer” whose services are free, universal, and accessible to all humans without discrimination.1 In reality, however, American society distributes nature’s benefits—and the effects of its destruction and decline—unequally by race, income, and age.

The nation’s recent reckoning with racism and violence against Black people has brought environmental injustices and disparities into long-overdue focus. The stories of Christian Cooper, threatened with violence and arrest while bird-watching in Central Park, and Ahmaud Arbery, murdered while jogging down a tree-lined street in coastal Georgia, are among the countless stories of Black, brown, and Indigenous people who, while seeking to enjoy the outdoors, have been threatened, killed, or made to feel unsafe or unwelcome.2

Meanwhile, long-running environmental injustices, such as the concentration of toxic air pollution and water pollution near communities of color, have been exacerbated by the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, with Black, Indigenous, and Latino communities experiencing higher virus-related hospitalization and death rates than white communities.3 Further, in many parts of the country, the coronavirus pandemic has exposed an uneven and inequitable distribution of nearby outdoor spaces for recreation, respite, and enjoyment. Particularly in communities of color and low-income communities, families have too few safe, close-to-home parks and coastlines where they are able to get outside.4 At this time of social distancing, when clean, fresh air is most wanted and needed, nature is out of reach for too many.

The unequal distribution of nature in America—and the unjust experiences that many people of color have in the outdoors—is a problem that national, state, and local leaders can no longer ignore. With scientists urging policymakers to protect at least 30 percent of U.S. lands and ocean by 2030 to address the biodiversity and climate crises, now is the time to imagine how, by protecting far more lands and waters over the next decade, the United States can guarantee every child in America the opportunity to enjoy the benefits of nature near their home.5

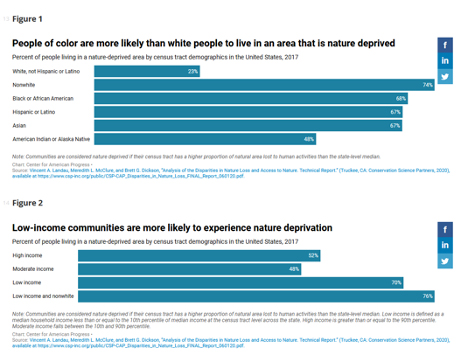

Using a new analysis by Conservation Science Partners (CSP), commissioned by Hispanic Access Foundation (HAF) and the Center for American Progress, this report examines the distribution of America’s remaining natural areas to understand the types and extent of disparities in nature access that exist in the United States.6 This report is intended to supplement, not supplant, the many individual voices and grassroots efforts that have been calling out and working to solve the many inequities and injustices in American natural resource policy. The data in this report help confirm the scale of racial and economic disparities in U.S. nature access. In particular, this report finds that the United States has fewer forests, streams, wetlands, and other natural places near where Black, Latino, and Asian American people live. Notably, families with children—especially families of color with children—have less access to nature nearby than the rest of the country. In other words, these communities are nature deprived.

These disparities are particularly concerning because nature is not an amenity but a necessity for everyone’s health and well-being. In the places where human activities in the United States have destroyed the most nature, there are fewer trees to filter the air and provide shade on a hot day; there are fewer wetlands and marshes to clean the water and to protect communities from floods and storm surges; there are fewer parks where children can grow their curiosity and fewer trails where adults can stretch their legs; and there are fewer public spaces where people of all races, cultures, and backgrounds can forge the common experiences and understandings that build respect, trust, and solidarity.7

To correct for the inequitable distribution of nature in America, among other barriers8 that racially and economically marginalized communities as well as LGBTQ and disabled people face to accessing the outdoors, this report puts forth several recommendations for policymakers to consider, including: creating more close-to-home outdoor opportunities in communities of color and low-income communities; changing hiring and workplace practices in government agencies, nonprofits, and foundations to create more representative leadership teams, boards, and staff; improving consultation with tribal nations and pursuing more opportunities for tribal co-management of natural resources; and working to overcome the nature gap among children by bolstering education and outreach programs. Broadly, however, the findings of this report affirm an urgent need for the United States to pursue an ambitious goal of protecting at least 30 percent of lands and ocean by 2030—and to do so in a way that ensures that nature’s benefits are more evenly and fairly distributed among all of the nation’s communities.

This report examines ethnic, racial, economic, and other demographic disparities in the current distribution of natural areas in the United States. It does not, however, pretend to offer a satisfactory or comprehensive answer to the questions of how and why these disparities emerged. Still, these questions are vitally important, and a deep-rooted body of scholarship and activism sheds light on the systems of power and white supremacy that have caused these disparities to emerge.9

One thing is worth stating upfront: The inequitable distribution of nature’s benefits in the United States is not the result of a consenting choice of communities of color or low-income communities to live near less nature, to allow more nature destruction nearby, or to give up their right to clean air and clean water.10 Nature deprivation is, instead, a consequence of a long history of systemic racism.

The data that CSP developed cannot be adequately analyzed without keeping this context of environmental racism in mind, including the following realities:

- Discrimination and racism in the United States have had profound effects on human settlement patterns and on the patterns of protections for the nation’s remaining natural areas. Redlining, forced migration, and economic segregation are just a few of the unjust policies and forces that have created barriers to, and a gradient of distance from, the United States’ remaining natural areas for people of color.11

- The history of public lands in the United States is rooted in the violent dispossession of lands from Native Americans. For centuries, settler-colonists on the North American continent displaced tribes from their ancestral homelands and engaged in the deliberate destruction of vital natural resources—many with economic and cultural significance—as a tool of genocide against the Indigenous population.12 This legacy continues in the U.S. government’s repeated failure to live up to its obligations to Indian Country that are enshrined in the treaties through which it acquired large swaths of Indian land.13 The federal government is legally required to ensure that tribes can access natural resources to protect their sovereignty, culture, and economic well-being.14 Too often, however, the government has sanctioned development that threatens sacred sites, weakens and circumvents tribal consultation, and ignores tribal concerns around environmental degradation.15

- Historically, the United States has systematically segregated and excluded people of color from public lands and other natural places. Black people have experienced segregation from the Civilian Conservation Corps to the National Park System; the nation’s public lands, beaches, and other natural areas have also been venues in which communities of color have been the subject of legalized and institutionalized racism.16 The legacies of this exclusion persist in many forms, including in the continued underrepresentation of people of color in hiring at natural resource agencies as well as in the histories of different groups represented by national parks and public lands. It also affects visitation to national parks and other public lands and participation in outdoor recreation, as well as causes people of color to feel unwelcome or in danger in nature.17

- People of color have been and continue to be the subject of violence, intimidation, and threats while in nature. The broader societal criminalization of people of color—and the accompanying threat of police brutality and even murder—can be exposed in parks and public lands.18 Participants in outdoor activities face the risk of being targeted, stereotyped, and harmed for simply enjoying nature or even trying to protect it, as was clear in the case of Christian Cooper.19 Experiences such as his led to the coining of the phrase “Birding While Black” to describe the risk, difficulties, and alienation that people of color endure in certain outdoor spaces.20

- People of color have traditionally been excluded from the U.S. conservation movement. For more than a century, the movement to protect parks, public lands, and other natural places in the United States has been dominated by white people and perspectives.21 Discrimination and the framing of conservation priorities through this exclusive lens—bolstered by underrepresentation of people of color at the staff and leadership levels of conservation organizations, foundations, and natural resource agencies—has perpetuated the racial divide in nature access.22

It is important to recognize that people of color have long experienced unequal access to nature. The United States must not perpetuate existing inequities, which have a real cost in terms of the health and economic well-being of these communities.

“THE NATURE GAP” originally appears at the Center for American Progress. Weekly “CAP Corners” happen on WURD’s “Reality Check”