The planet has been so preoccupied with the pandemic that many of us forgot about the destructive effects of climate change.

Croix Ellison | Guest Commentary

The planet has spent so much time preoccupied with pandemic, for obvious reasons, that it seemed to forget all about climate change. As time moves on and more natural disasters in the form of droughts, heat waves, major floods, hurricanes and tornadoes in strange places reveal themselves, climate change will yet again strike our communities. One of its most deadly forms that we’re dealing with right now: extreme heat waves. As Climate Central reports: “Recently, the mercury in Death Valley, Calif. climbed to a blistering 128℉ ーthe hottest temperature recorded on earth since 2017. Shortly after, NASA and NOAA announced that global temperatures from the first half of 2020 are the 2nd-hottest on record, just behind 2016. Greenhouse gas emissions are changing the chemistry of the atmosphere, causing our climate to warm to a level that modern society has never experienced.”

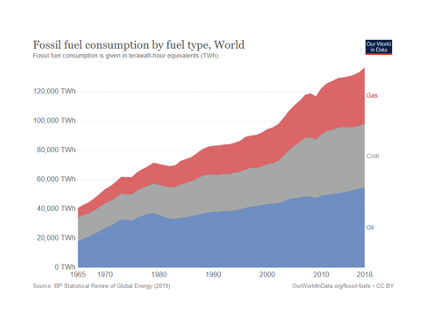

While many communities were forced to stay-at-home as a precaution against coronavirus infection, we were all misled into a false sense of security about climate change. More people at home meant a major drop in commutes or reasons to go outside, use a car and travel to work. That led to a major drop in emissions, especially in major cities. Major modes of transportation responsible for spewing huge amounts of carbon emissions – which are behind human-made climate change – were dramatically limited in use. The skies above major cities turned from polluted haze to a remarkably clear plate of blue. However, as Rice University’s Daniel Cohan observed: “The air is getting cleaner, although these blue skies may be temporary. But it isn’t getting cooler. The buildup of greenhouse gas pollution continues, and global temperatures are still rising. You may have seen maps in the news showing blotches of air pollution that have shrunk since economies started shutting down in the past few months. Most of those maps are plotted from satellite observations of nitrogen dioxide, or NO2, a gas that triggers respiratory illnesses such as asthma. It also reacts in the air to form other types of pollution, such as smog, haze and acid rain. [But] what about carbon dioxide, or CO2, the leading cause of global warming? As we breathe cleaner air and see less haze, is that falling too? Unfortunately, no.”

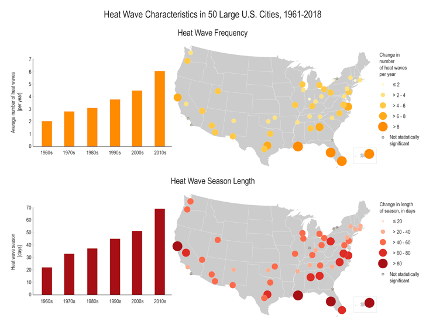

That will mean heat waves, which have been on the rise historically, are not going anywhere to the surprise and chagrin of many. The trend has been unstoppable since the 1960s (and coinciding with the rise in large scale manufacturing and fossil fuel use).

Scientists were already warning, as the pandemic continued that rising heat trends would continue into 2020, making it one of the hottest years on record.

As a result of these increasingly frequent heat waves, the nation will be facing additional health challenges, further complicating efforts to contain the pandemic. In the country’s hope to transition out of COVID-19 (we emphasize hope because infections are still, as of this BEnote, still on the rise and are potentially reaching a tipping point where they may be uncontrollable), extreme heat will be especially difficult to shelter from this year. It will become a serious risk and will disproportionately threaten lower-income communities whose access to air conditioning is typically limited. Drexel University’s School of Public Health epidemiologist Yvonne Michael offers perspective on this in a recent WHYY (Philadelphia) report: “Noticeably, the groups that are at higher risk for the increased illness and death associated with extreme heat are very similar to the groups that are at high risk for poor outcomes with COVID-19, with the exception of the young children.”

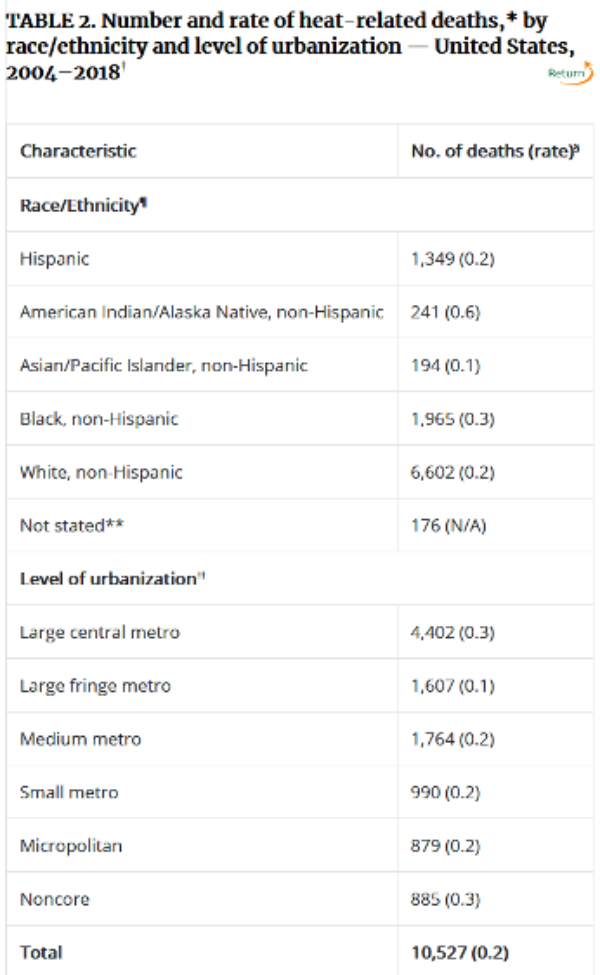

Judging from the patterns of previous years, heat temperatures will continue to become hotter and longer. In addition, they will continue to manifest into a leading public health threat. In fact, heat waves are known to have caused more than 10,500 deaths in the U.S. between 2004 – 2018, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. All racial demographic groups are impacted, but as the table below shows, Indigenous Americans, Black Americans and Latinos – in this order – are the most disproportionately impacted.

Globally, researchers have estimated that there were 166,000 heat-related deaths worldwide between 1999-2017, which surpasses the death tolls of tornadoes, hurricanes, and floods.

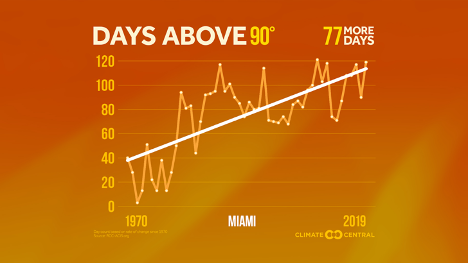

From our heat patterns over just the past fifty years, extreme temperatures look much more dangerous today.

Although the meaning of “extreme heat” is defined differently in every city, temperature levels have still exceeded and increased across the entire nation. Furthermore, Greenhouse Gas emissions – such as methane, which accelerates the warming – are changing our planet’s atmosphere, which is actively causing our Earth’s global temperatures to change to concerning levels our society is not used to experiencing.

In recent years, many parts of the country, including cities hardest hit by heat waves, have made efforts and protocols to protect citizens from the consequences of extreme heat. However, for the past few months, there has been so much emphasis on coronavirus, particularly as governments on the local, state and federal levels face the worst revenue shortages since the Great Depression, that policy makers have yet to prepare for and are not equipped to deal with another record setting heat wave.

Over the course of the COVID-19 quarantine, our atmosphere experienced a dip in pollution and an improvement of the environment’s air quality due to a decrease in carbon powered machines Fewer people are commuting all over the world. Traffic nowadays is limited to mostly essential trips, even as reopening happens. Some travel bans still restrict international flights. Canceled conferences, festivals, concerts and other public events have diminished tourism. Additionally, airline ridership has slumped altogether and airports are seen to be near empty. In China, a leading carbon emitter, experts estimated a 25 percent drop in carbon emissions.

Still, there is no way of taking back the emissions that have already been put into the air. As a result of the lack of effort to cut our carbon emission in previous years, there is no way to turn down our global thermostat back to the way it was naturally. Policymakers should, however, devise strategies now to reduce the impacts. That doesn’t include rolling back key legacy environmental regulations. It means they will need to expand on them while reviving major provisions in global standards such as the Paris Climate Agreement. For now, with pandemic a priority, it’s hard to predict when that will be prioritized.

CROIX ELLISON interns for the Council of State Governments Eastern Regional Conference Council on Communities of Color.