Charles Ellison | ecoWURD | Analysis

As the spread of COVID-19 continues to escalate and the United States has become the global epicenter of the pandemic, there is currently no available demographic data related to race and income on coronavirus infection cases and deaths. We are unable to get a better glimpse of who’s infected and who’s dying from this virus based on their race and income – despite a healthy stream of data offering insights into patterns based on gender and age.

The gender and age data, however, offer just a fraction of the total story. Available race and income data could offer even greater insights into factors which explain elevated risk for COVID-19 infection and morbidity. This dramatically changes the analysis and conversation on the pandemic. We already know, for example, that racial bias plays a significant, and destructive role, in the application of healthcare for Black patients. An October 2019 study released in Science revealed that “[h]ealth systems rely on commercial prediction algorithms to identify and help patients with complex health needs. We show that a widely used algorithm, typical of this industry-wide approach and affecting millions of patients, exhibits significant racial bias: At a given risk score, Black patients are considerably sicker than White patients, as evidenced by signs of uncontrolled illnesses. Remedying this disparity would increase the percentage of Black patients receiving additional help from 17.7 to 46.5 percent.”

Another September 2019 study in the New England Journal of Medicine showed what we already knew anecdotally and instinctively, that: “Overall, 61.3% of white patients were transported to the nearest emergency department. In adjusted analyses, this proportion was 5.3% lower for black patients and 2.5% lower for Hispanic patients. The difference was most pronounced in areas with a higher density of hospitals. An analysis of walk-in ED visits among the Medicare population revealed the same trend: Fewer black and Hispanic patients presented to the reference ED compared with white patients.”

These observations present critical questions in today’s pandemic environment: how will these bias trends present themselves or play out during the pandemic? It’s not a question of if they will – it’s a bigger question of how bad.

It’s too early to tell in any specific way, since we can’t identify patients by race or income. But, what we can see, based on the data collected thus far, is that there is a disproportionately high level of COVID-19 infection case and death rates in states and metropolitan areas with already large clusters of Black residents or places that either match or exceed the Black population proportion in the United States of 13 percent. These are also places where those same Black populations already face systemic treatment bias in the healthcare system.

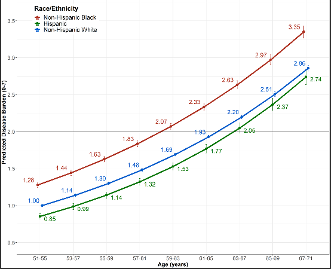

The other big issue is that before coronavirus, Black populations were already hit with the highest chronic disease ailment and morbidity rates compared to any other racial demographic. Hence, Black populations are in a higher risk bracket for COVID-19 infection and death due to these pre-existing conditions. “Whereas the last 50 years has resulted in important longevity gains for older adults in the U.S. these improvements have not been universal,” researchers concluded in a July 2019 study published in science journal PLOS ONE. “Slowed and even worsening trends for the most vulnerable older adults are evident, a regrettable and distinct trend that stands in contrast to other high-income countries. Indeed, older at-risk adults—among them women, underrepresented racial and ethnic minorities, and adults with low educational attainment or low socioeconomic status—are living for extended periods of their lives in sicker and more disabled states and are at greatest risk for premature morbidity and mortality” The figure shown below (from that study) illustrates how dramatic the “predicted disease burden” is for Black individuals compared to Whites and Latinos …

“One big thing we need to look at, as well, are these high comorbidity rates that were prominent in our communities long before COVID-19,” Dr. Frederick Corder, a D.C.-area based pediatrician told ecoWURD. “Hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease and other issues really aggravate this situation.”

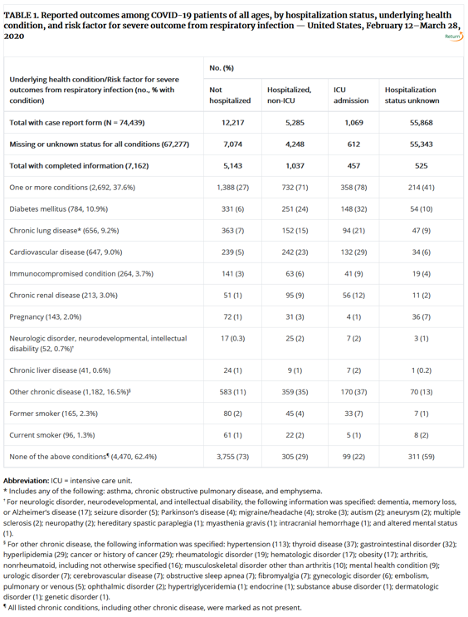

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) just released a new report this week warning that it will. An analysis of data from COVID-19 case loads nationwide showed “…. higher percentages of patients with underlying conditions were admitted to the hospital and to an intensive care unit than patients without reported underlying conditions. These results are consistent with findings from China and Italy, which suggest that patients with underlying health conditions and risk factors, including, but not limited to, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, COPD, coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, chronic renal disease, and smoking, might be at higher risk for severe disease or death from COVID-19” The findings are shown in the table below …

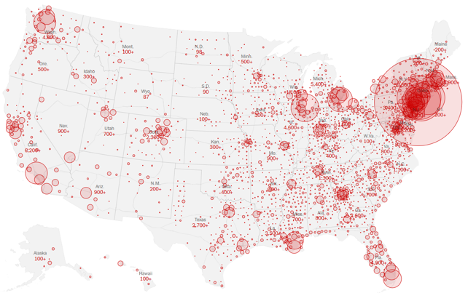

We can initially ascertain from a quick look at the NY Times coronavirus case map below: places exhibiting high numbers of confirmed COVID-19 cases are not just largely urban areas, but they are places usually associated with very diverse and notably large Black population centers and communities. These places are historically characterized by distressed economic conditions and high poverty, as well as high chronic disease rates, lack of access to adequate healthcare resources and food security.

A deeper analysis will unveil some troubling patterns. We know that, officially, 13 percent of the overall U.S. population identifies as “Black” or of African-descent. COVID-19 case data (as collected and curated regularly by the NY Times) show us that 70 percent, or 14, of the Top 20 states with the highest number of confirmed coronavirus cases (as of this writing) are places where the Black residential population either matches or exceeds the national proportion – or, the state’s Black population is at or above 13 percent. Those states, shown below with corresponding numbers of cases, include (as of 4.1.20) …

- New York (76,030)

- New Jersey (18,696)

- Michigan (7,630)

- Florida (6,741)

- Louisiana (5,237)

- Pennsylvania (4,997)

- Georgia (4,117)

- Texas (3,576)

- Connecticut (3,128)

- Ohio (2,199)

- Tennessee (2,049)

- Maryland (1,662)

- North Carolina (1,528)

- Wisconsin (1,351)

States like New York, New Jersey, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Louisiana, Georgia, Ohio, Tennessee, Maryland, North Carolina and Wisconsin contain major cities or counties and metropolitan areas famously known for their massive Black population concentrations. These are places like: New York City, NY; Newark, NJ; Detroit, MI; Philadelphia, PA; New Orleans, LA; Atlanta, GA; Cleveland, OH; Memphis, TN; Prince George’s County, MD; Charlotte, NC; and Milwaukee, WI. Most of these locations are either half Black or majority-Black. Interestingly enough, counties like Prince George’s (which is 65 percent Black) also contain the largest concentration of Black “middle-class” residents in the nation – yet, right now, Prince George’s County claims the highest COVID-19 related death rates in the state of Maryland. One evident problem is lack of access to hospitals and emergency units.

When we look at statewide death rates, 60 percent – or 13 – of the Top 20 states by number of coronavirus deaths are states where the Black population matches or exceeds the national proportion. Those states – ranked by corresponding death rates as of 4.1.20 – include …

- New York (1,552)

- New Jersey (267)

- Michigan (264)

- Louisiana (240)

- Georgia (125)

- Illinois (107)

- Florida (85)

- Pennsylvania (72)

- Texas (57)

- Ohio (55)

- Virginia (27)

- South Carolina (22)

- Mississippi (20)

The NY Times data also includes snapshots by nearly all counties in the United States. There are a dozen counties throughout the U.S. where the number of coronavirus cases has surpassed the 1,000 mark. Ten (10) of those counties – or 83 percent – are jurisdictions where the Black residential population matches or far exceeds the national population proportion. To date, those counties – with corresponding case numbers and Black population percentages – include …

| County | State | Cases

(as of 4.1.20) |

Black Population % |

| New York City | NY | 43,139 | 25% |

| Westchester | NY | 9,967 | 17% |

| Cook | IL | 4,496 | 24% |

| Wayne | MI | 3,735 | 39% |

| Miami-Dade | FL | 2,123 | 18% |

| Essex | NJ | 1,900 | 42% |

| Orleans | LA | 1,834 | 60% |

| Fairfield | CT | 1,870 | 13% |

| Suffolk | MA | 1,373 | 25% |

| Philadelphia | PA | 1,315 | 44% |

There are 29 states identified in this analysis that contain counties with large Black population centers. Many of these counties are also exhibiting the highest COVID-19 death rates in their respective states. Within those 29 states, there are 25 counties with Black population counts that match or are higher than the national proportion of 13 percent. Five (5) of these counties have experienced more than 20 COVID-19 related deaths. For more context, I’ll also provide the corresponding poverty rates for those five counties displayed in the table below …

| County | State | Deaths

(as of 4.1.20) |

Black Population % | Poverty rate |

| New York City | NY | 1,096 | 25% | 19% |

| Orleans | LA | 101 | 60% | 24% |

| Wayne | MI | 120 | 39% | 22% |

| Cook | IL | 61 | 24% | 14% |

| Fairfield | CT | 38 | 13% | 10% |

Keep in mind that the national poverty rate, as of the most recent Census data, is near 12 percent (although other estimates, such as those from the Kaiser Family Foundation, put it at 13 percent). About 80 percent of those counties highlighted in the table above, 4 out of 5 of these counties, struggle with poverty rates that exceed 20 percent, thereby surpassing the national average.

We are unable to extract any more specific conclusions since counties and states are not, at the moment, actively tracking race and income. Still, we can generate enough correlations from mapping data to show that the extent of COVID-19 damage will largely depend on what zip code you live in. “And when you compact Black, low-income populations in urban areas, you’re going to have a much more difficult time managing an outbreak crisis,” notes economic strategist Mike Green of ScaleUp Partners during an episode of WURD’s Reality Check. “So where do we direct our resources?”

WURD Radio is one of more than 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on economic mobility. Read more at brokeinphilly.org or follow at @brokeinphilly.