So far, the public discourse on coronavirus is focused on middle-class inconveniences and political spats.

Even as cities and states such as Philadelphia go into a more extreme “stay-at-home” lockdown posture, conventional media coverage around the impact of coronavirus remains a very White middle-class affair.

Of course, society-at-large understands how severe the pandemic is, how fast it’s spreading, and it’s comparatively very high kill rate compared to the flu. Yet, the public conversation around it centers more on what’s inconvenient and who’s been inconvenienced than the still immeasurable destruction in more exposed communities that’s taking place.

Hence, “corporate” media coverage has not been holistic, all that responsible or responsive or compassionate. The only audiences that appear to count are mostly White, somewhat affluent and frantically managing coronavirus as a bump in the road. So, if it’s not tips on social distancing and the merits of remote work, it’s how quarantines will lead to baby booms or divorce, or the benefits of life “slowing down,” or how we’ll need to use parks, it’s listicle-size shaming efforts showing who failedat social distancing and celebrities pulling a fool on social media … or it’s politicians distance hugging their celebrity friends, or the thousands, despite warnings, who couldn’t stay still and went for a cherry blossom stroll anyway. When it’s not all of the above, reporters are obsessed with useless White House briefings spreading misinformation or open political spats between lawmakers.

Some of this is occasionally informative and, perhaps, for a few moments, worth a light, entertaining distraction. But, such coverage has – as it has traditionally done with news of climate change disasters – put the collective experience of more distressed, low-income and frontline populations on the backburner. Even as a quarter of Philadelphia residents, for example, are marginalized by deep poverty, their individual stories of struggle and resilience (while faced with impending economic meltdown) are marginalized as well. Many of these first weeks of social distancing, self-quarantining and the shutdown of essential businesses (while streets became ghost towns) were captured in media portraits of young urban professional adventurism. The gravity of what’s transpiring in more distressed hoods and settings has not settled in … at all – local news outlets aren’t venturing into Philly’s Nicetown section or Washington, D.C.’s Anacostia neighborhoods. This is no different from how New Orleans’ low-income Black communities were completely forgotten and left behind during Hurricane Katrina in 2005 – until it boiled over to the point where no one, including the president, could ignore it anymore.

It’s important media resist the temptation to portray coronavirus as a frantic moment for the well-to-do (and the famous who manage to get their hands on testing kits while the rest of us, and especially the least of us, can’t). That kind of public discourse leads to policymakers ignoring the places where need is critical. It creates a recipe for more focus on emergency efforts that attend to corporate priorities more so than urgent worker needs: as is seen in the failed rushing of a proposed $2 trillion federal stimulus package in the Senate versus a much more worker-friendly, vulnerable population-responsive package of proposals from the Congressional Black Caucus. It also prompts others to ignore racial and class fault lines even as their dramatic policy pivots are viewed as “leadership”: such as New York Governor Andrew Cuomo’s decision to temporarily suspend mortgage payments for homeowners throughout the state, including New York City, but doing nothing for renters – even though 65 percent of New York city residents rent. On the federal stage, there’s a movement to halt evictions, but noneto stop rent.

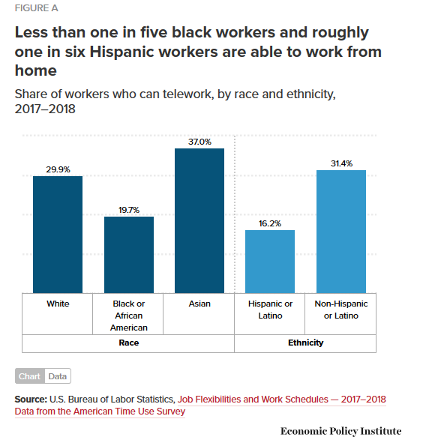

But, not everyone can remote work or has had the capability to remote work as the national coronavirus conversation assumes. Stay-at-home is not that simple, and can be downright tragic, when we fully understand the complexities of living faced by Black populations that are too often confronting economic distress. Even Black “middle class” families still accumulate twice as less as their White counterparts, as the Urban Institute illustrates, generational wealth being a much bigger hurdle in the present and the future for Black households than everyone else. Income, professional and asset holding opportunities are not as abundant, which leads to a landscape where less than 20 percent of Black workers are able to work from home compared to nearly 30 percent of White workers, as shown recently by the Economic Policy Institute.

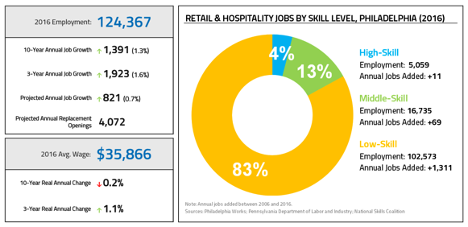

This presents a grim picture for economically handicapped places where poverty is famously rampant. Jobs that are “telework” prohibitive such as the combined retail and hospitality industry account for 20 percent of all jobs in the United States. In Philadelphia, retail and hospitality accounts for about the same percentage of all jobs citywide, according to the Economy League …

Most of those hardest hit will be in Black populations as those sectors collapse due to the pressures of coronavirus, despite the face of media coverage showing otherwise. Bad enough Black labor participation in places like Philadelphia is already lower compared to other populations, along with high unemployment. Policymakers will need to take this into account to legislate and enforce accordingly, but there must be a public conversation – encouraged by media coverage – putting pressure on them to do so.

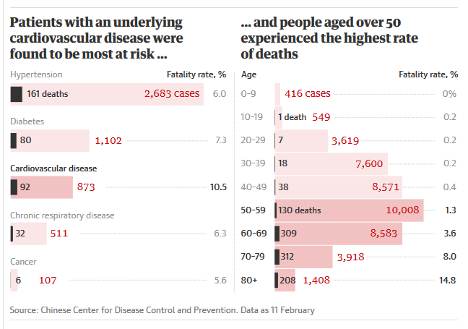

Other underreported equity aspects of the coronavirus epidemic also include the reality of populations long stressed by chronic disease and polluted environments. Coronavirus, after all, attacks the respiratory system aggressively, and the risk of death from infection rises dramatically in individuals suffering from an array of chronic diseases ranging from diabetes to high blood pressure – conditions that are much more prevalent in Black communities. Coronavirus also adds yet another layer of stress to communities already grappling with chronic disease, cancer and mortality rates while living in major air pollution zones. Initial data coming out of China – which is infamous for its high air pollution – shows a greater risk of death from coronavirus infection among individuals affected by hypertension, diabetes and cardiovascular diseases.

According to initial research, the data is still inconclusive on enhanced risks from asthma for coronavirus. “So far, there has been little information on people with asthma with COVID-19,” notesMitchell Grayson, M.D. a leading allergist and immunologist at Nationwide Children’s Hospital and chair of the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America’s Medical Scientific Council. However, Grayson does caution that a viral infection which impacts the lungs and respiratory system – which includes coronavirus – can become asthma triggers: “There are viruses that have been associated with the development of asthma and postviral wheeze, and then there are viruses associated with asthma exacerbations. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), rhinovirus, coronaviruses, and influenza have been associated with postviral wheeze and asthma onset.” Still, asthma rates among African Americans are the highest in the nation, on every age and gender scale, with Black individuals and children dying from the condition more than any other demographic group. Communities that live with high asthma prevalence become extremely vulnerable. That begs deeper research into real linkages between coronavirus and asthma, with a special focus on Black communities and the various environmental and economic stressors aggravating those conditions.

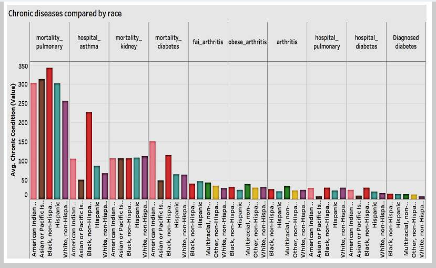

The mortality rates for those chronic conditions, aggravated by air pollution, are already high among Black populations, as a 2019 empirical study by Fordham University shows below. These gaps are historically widened by disparate and racist treatment of Black patients in healthcare systems and facilities. As hospitals become increasingly overwhelmed by the number of severe coronavirus cases, questions arise as to who will get preferential treatment and care. Concerns are already growing that, because of implicit bias among healthcare practitioners and institutions, Black individuals may be less likely to receive testing.

Given these variables and others, the public conversation must make every effort to put a bigger spotlight on these disparities. The mainstream media’s tendency to reflexively trivialize various angles of a crisis with puff reporting about middle class inconveniences only exacerbates the risk. Those who are already forgotten become more forgotten. This will not only be a missing conversation, but it potentially leads to many more infections and deaths that would have been avoidable had only communities and policymakers been made aware or pushed to look in their direction.

WURD Radio is one of more than 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on economic mobility. Read more at brokeinphilly.org or follow at @brokeinphilly.